By then, he was already a cult figure locally: a poet and a writer who carried his work around in a plastic bag, even after his band found success.Īfter his death, Deborah stored the work in two large envelopes. He was an awkward, lanky figure who wore skinny jeans and eyeliner. The lyrics for Joy Division’s 1979 single Transmission, in Curtis’s distinctive capitalised handwriting Photograph: PRĭeborah met Ian when she was a teenager in Macclesfield. Unlike her own memoir, she says, this book is for Ian.

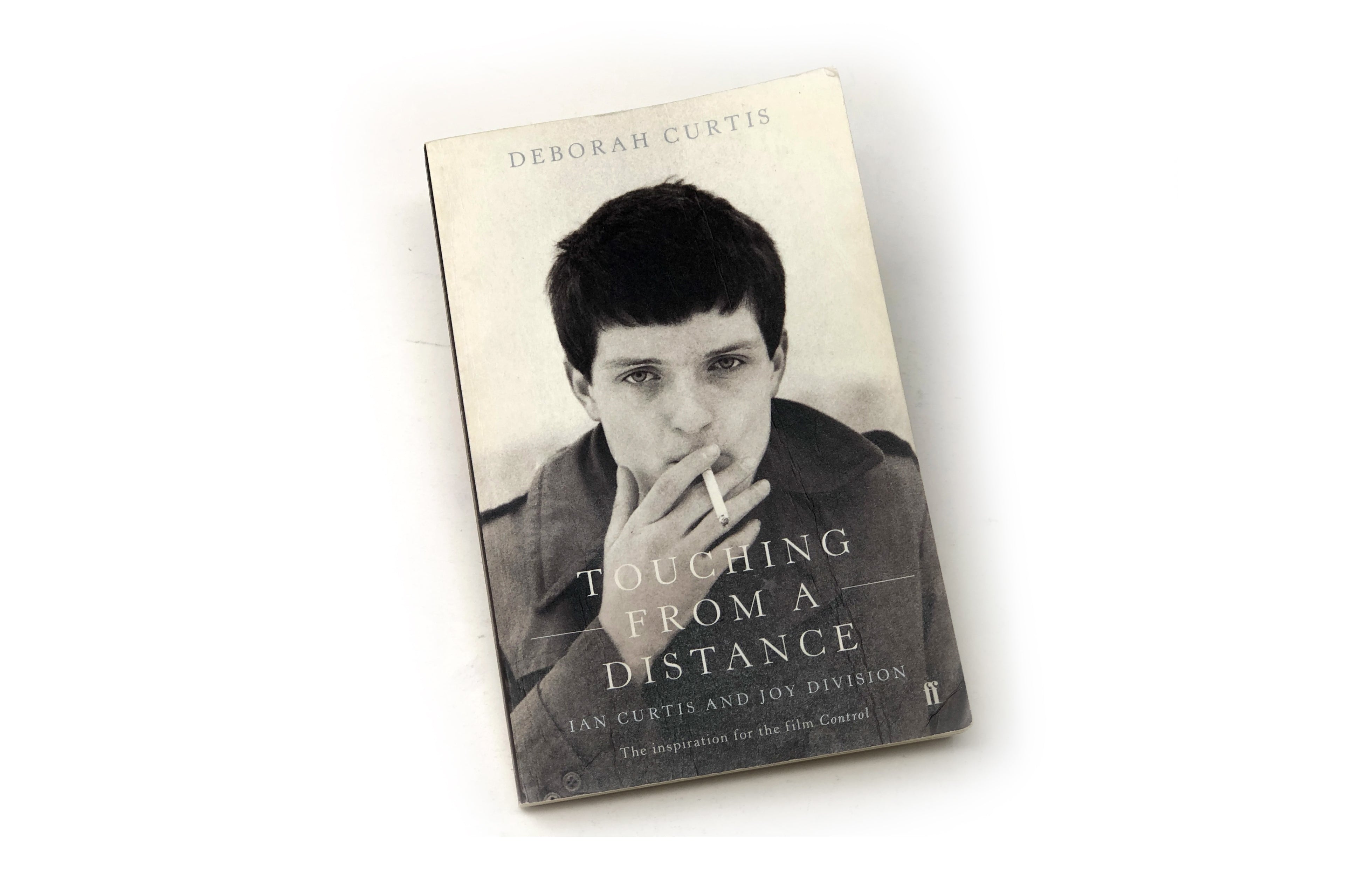

It has also been dissected on page and on screen, following Deborah’s memoir, which Anton Corbijn turned into the 2007 biopic Control. His life story – epilepsy, depression, extramarital affair – aches through songs such as Love Will Tear Us Apart and She’s Lost Control. He is the iconic frontman, whose band’s pioneering post-punk documented late 1970s Manchester in all its grit and grime. In the decades since, his brief but incendiary career has achieved cult status. He left behind a wife, a baby daughter, and a music career that had barely begun. Ian was 23 when he died, on the eve of Joy Division’s first US tour. It is an attempt, says Deborah, to showcase Ian’s writing in a way he would have wanted.

Featuring handwritten lyrics and prose drawn from his notebooks and scraps of paper he kept in ringbinders, the selection was put together with the help of journalist Jon Savage. He didn’t like songs that didn’t mean anything.”ĭeborah is talking about So This Is Permanence, a book out next week that gathers together writings by her husband Ian, the Joy Division frontman who took his life in May 1980. He used to talk about what the lyrics meant and the story behind them. “If he put a record on, we’d have to listen to absolutely everything. “W ords meant such a lot to Ian,” says Deborah Curtis.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)